K

Kathleen Martin

Guest

Federal researchers are hoping that a cheap, 21-pound glider with stubby wings will help them solve a daunting climate challenge: How to thoroughly explore the Earth’s upper atmosphere.

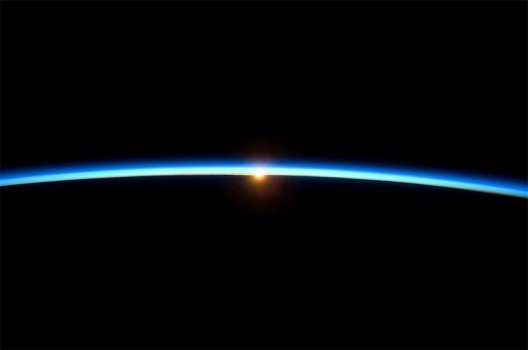

The stratosphere, which begins between 26,000 and 47,000 feet above Earth, depending on whether you’re at the poles or the equator, is home to the ozone layer, which protects people from harmful sun rays and is vulnerable to pollutants.

Major emissions of climate-warming greenhouse gases collect in the stratosphere, but at the moment it remains one of the least examined layers of the atmosphere. Weather balloons — the traditional tool for exploring the upper gases enveloping the planet — can get up there. They carry a packet of instruments that can measure the weather and identify, or even capture, samples of pollutants.

But that’s where the trouble begins, according to Colm Sweeney, who’s investigating the problem for NOAA.

Weather balloons deploy parachutes carrying instruments and their data, packed in a Styrofoam container. The parachute drops into the the lower atmosphere where it is often driven off course by high winds. They can often be sent into thick forest or sometimes the ocean.

“Then we have to go out and find it,” explained Sweeney in an interview.

Because the parachutes and their data are frequently lost, NOAA has refrained from using more expensive instruments in the stratosphere and has been reluctant to increase the number of ultra-high flights using balloons. At the same time, improved computer models require more data from the stratosphere to track the rise of global warming.

“We’ve been trying to find people to fix this for at least a decade,” Sweeney noted.

Three years ago, he called one of his former college professors, who suggested that Sweeney consult the professor’s son, who teaches a course in aeronautical design at Arizona State University.

The teacher, Timothy Takahashi, and one of his graduate students came up with the design of a smart, automated glider to carry the cargo. After being dropped from the balloon in very thin air, the glider’s wings help it gather speed so it can steer its way through high winds and return to its launch location.

That was the birth of HORUS, which stands for High-altitude Operational Return Unmanned System. The drone found a sweet spot in the often hyper-expensive economics of stratospheric exploration.

The prototypes of HORUS developed at Arizona University were cheap, made from fiberglass and foam. While the idea of a space glider seemed like an oxymoron to many people, Sweeney thought it might be built for less than $2,000.

“If you paid for an airplane to go up to 40,000 feet, it’s unlikely that you’re going to do that for less than $10,000,” he said.

Continue reading: https://www.eenews.net/articles/near-space-drones-search-atmosphere-for-climate-answers/

The stratosphere, which begins between 26,000 and 47,000 feet above Earth, depending on whether you’re at the poles or the equator, is home to the ozone layer, which protects people from harmful sun rays and is vulnerable to pollutants.

Major emissions of climate-warming greenhouse gases collect in the stratosphere, but at the moment it remains one of the least examined layers of the atmosphere. Weather balloons — the traditional tool for exploring the upper gases enveloping the planet — can get up there. They carry a packet of instruments that can measure the weather and identify, or even capture, samples of pollutants.

But that’s where the trouble begins, according to Colm Sweeney, who’s investigating the problem for NOAA.

Weather balloons deploy parachutes carrying instruments and their data, packed in a Styrofoam container. The parachute drops into the the lower atmosphere where it is often driven off course by high winds. They can often be sent into thick forest or sometimes the ocean.

“Then we have to go out and find it,” explained Sweeney in an interview.

Because the parachutes and their data are frequently lost, NOAA has refrained from using more expensive instruments in the stratosphere and has been reluctant to increase the number of ultra-high flights using balloons. At the same time, improved computer models require more data from the stratosphere to track the rise of global warming.

“We’ve been trying to find people to fix this for at least a decade,” Sweeney noted.

Three years ago, he called one of his former college professors, who suggested that Sweeney consult the professor’s son, who teaches a course in aeronautical design at Arizona State University.

The teacher, Timothy Takahashi, and one of his graduate students came up with the design of a smart, automated glider to carry the cargo. After being dropped from the balloon in very thin air, the glider’s wings help it gather speed so it can steer its way through high winds and return to its launch location.

That was the birth of HORUS, which stands for High-altitude Operational Return Unmanned System. The drone found a sweet spot in the often hyper-expensive economics of stratospheric exploration.

The prototypes of HORUS developed at Arizona University were cheap, made from fiberglass and foam. While the idea of a space glider seemed like an oxymoron to many people, Sweeney thought it might be built for less than $2,000.

“If you paid for an airplane to go up to 40,000 feet, it’s unlikely that you’re going to do that for less than $10,000,” he said.

Continue reading: https://www.eenews.net/articles/near-space-drones-search-atmosphere-for-climate-answers/